Guidelines for submitting articles to San Pedro del Pinatar Today

Hello, and thank you for choosing San Pedro del Pinatar.Today to publicise your organisation’s info or event.

San Pedro del Pinatar Today is a website set up by Murcia Today specifically for residents of the urbanisation in Southwest Murcia, providing news and information on what’s happening in the local area, which is the largest English-speaking expat area in the Region of Murcia.

When submitting text to be included on San Pedro del Pinatar Today, please abide by the following guidelines so we can upload your article as swiftly as possible:

Send an email to editor@spaintodayonline.com or contact@murciatoday.com

Attach the information in a Word Document or Google Doc

Include all relevant points, including:

Who is the organisation running the event?

Where is it happening?

When?

How much does it cost?

Is it necessary to book beforehand, or can people just show up on the day?

…but try not to exceed 300 words

Also attach a photo to illustrate your article, no more than 100kb

Monte Arabí in Yecla - prehistoric rock art and a multitude of legends

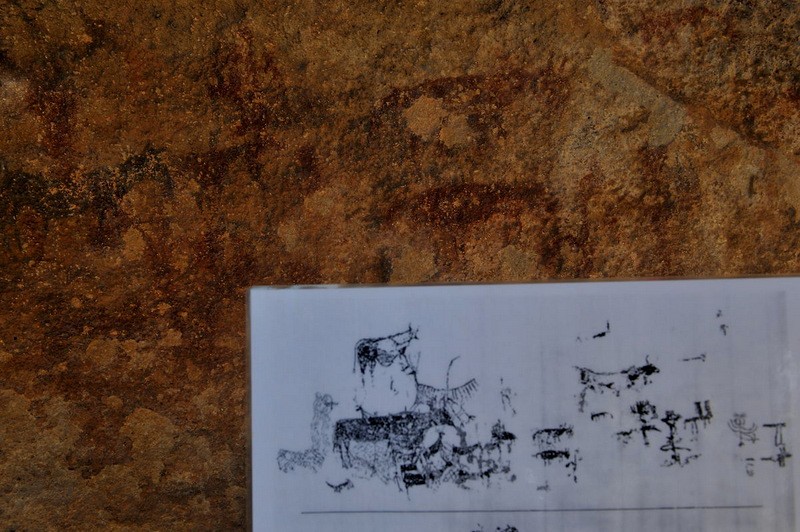

Rock art at the sites in Yecla show several different periods of Prehistoric rock art

The archaeological sites at the mystic mountain of Monte Arabí in the municipality of Yecla are considered among the most important in the Region of Murcia, containing prehistoric art from different periods and providing evidence of sophisticated human habitation here well before the start of the Copper Age in Europe.

The archaeological sites at the mystic mountain of Monte Arabí in the municipality of Yecla are considered among the most important in the Region of Murcia, containing prehistoric art from different periods and providing evidence of sophisticated human habitation here well before the start of the Copper Age in Europe.

The whole rural area is served by a tourist infomation point on the southern side of the mountain.

Monte Arabí

Monte Arabí dominates the northern side of the plateau on which Jumilla and Yecla stand (the “Altiplano”), which forms a corridor between the north of the Region of Murcia and the Comunidad Valenciana. The area is at altitudes between 700 and 800 metres above sea level and Monte Arabí stands high above them, 1,068 metres above sea level at its highest point, overlooking the vineyards below.

The views from the mountainside are breathtaking, and there can be little doubt that prehistoric man chose the site with the spiritual significance of the location in mind, either consciously or subconsciously. There are prehistoric paintings here dating back to the earliest era of European rock art more than 8,000 years ago as well as petroglyphs and "cazoletas", both forms of prehistoric carving, spread across different areas of Monte Arabí.

A car is required to visit the area but there is parking at the foot of Monte Arabí and visitors can follow a number of suggested walking routes from this point, the main one being the PR-MU91 (click here) route which takes walkers on a 5.3-km tour of the most important areas of this beautiful and imposing part of the Yecla countryside.

The three different sets of prehistoric rock art have been protected by fencing in order to prevent them paintings from damage. They cannot be seen by the general public on a day-to-day basis but from time to time the archaeological museum and tourist office run guided tours and large groups can ask the tourist office for special access with a guide.

The two rock shelters of Cantos de la Visera are close to the car park and are more accessible for groups, but the Cueva del Mediodía is higher up and is more difficult to reach. Both sites can only be visited in the company of a guide.

Just above them is the spectacular Cueva de la Horadada and the area of rock known as the “sea of Yecla” by locals, both offering stunning potential for photographers and with fabulous views, an excellent focal point for an excursion to Monte Arabí.

Monte Arabí is also home to the remains of a fortified Bronze Age settlement (“El Arabilejo”) dating from the second millennium BC, and areas of associated engravings and cup-marks in the rock (petroglyphs and cazoletas), making this one of the most important prehistoric complexes in eastern Spain.

Rock art at Cantos de la Visera and Cueva del Mediodía

There are reasons why the rock shelters of Cantos de la Visera and Cueva del Mediodía might have been chosen by prehistoric man in which to paint their art, and visitors immediately gain a sense of how the natural rock formations lend themselves as a natural surface on which to paint, but the dominant position on the hillside, with views down over the hunting lands of the earliest residents of Yecla, would have required a conscious effort to access.

Levantine Art of the period between 8,000 and 3,500 BC was typically created either in shelters of this kind, with a ledge protecting the cavity from the elements, or in shallow caves, both of which allow sunlight in to a sufficient degree for the artist to work and for others to see the results.

There are four accepted periods in rock-art of this time:

- Naturalistic (lineal geometric), 6,000 BC

- Stylized static or macro schematic, 6-5,000 BC

- Stylized dynamic or levantine naturalist, 5-4,000 BC

- Final phase of transition to the schematic, 3-2,000 BC

No-one knows exactly why the paintings were made - whether this was a ritual act, whether the act of painting was accompanied by any other activity, whether painting was undertaken at a specific time of year or by specific members of a group. Excavations have confirmed that there are no signs of burial at these sites, although there is evidence of fire over a prolonged period (some of it modern!).

What is known is that the paintings required significant effort to produce, as the “paint” required planning and preparation and the locations are always difficult to access. The forms of objects and animals portrayed are reproduced in different locations in the same style fairly consistently.

At Monte Arabí, while there is evidence of human habitation nearby during this period there is none on the mountain itself, indicating that this site was kept apart from the daily lives of the inhabitants.

The paintings were discovered in 1912 by Julián Zuazo Palacios. At the shelter of Cantos de la Visera there are two rocks or rock faces containing examples of Levantine Art, the first featuring at least 30 representations of what appear to be large herbivores like horses and cows and the second showing around 70 designs. Here the range extends to include ibex and deer, and there are also schematic figures which appear to represent humans, indicating that later paintings fall into the category of Iberian schematic art.

This site also has the only representation of a bird found anywhere in Spain at this period.

The main colouring used is red, with various shades being due to impurities in the mix which darkened the colour.

At the Cueva del Mediodía, a cavity protected by an enormous overhanging ledge on the side of the mountain higher up on Monte Arabí, there are various small cave spaces which could have been used as shelters, and inside there are three groups of prehistoric paintings.

In dark red there is a collection of zig-zag lines and a group of human figures with their arms linked, in yellow a collection of schematic images including a human figure and a palm tree, and in bright red there are highly stylized figures of a horse, two humans and numerous schematics alongside a goat and a double-headed axe. Many of the designs are T- and Y-shaped, with horizontal crosses.

The cave was given its name because it faces south, and at midday the overhanging ledge leaves the shelter entirely in the shade: in the past those tending their crops on the plain below used this as a sign that it was time to break for lunch.

Types of rock art found at Monte Arabí

Levantine art is a kind of prehistoric pictorial art which is common at the group of sites included in the Unesco World heritage Site entitled “Prehistoric Rock art of the Iberian Mediterranean Basin”, including the Monte Arabí sites. Images consist mainly of small painted representations of human and animal figures, the earliest of their kind in Europe, and UNESCO specifies that Levantine art dates from approximately 10,000 years to 5,500 years ago. In other words, the paintings were created over a timespan too long for us to imagine comfortably, and are the work of over 200 generations of prehistoric men belonging to hunter-gatherer cultures.

The artists may have been trying to conjure up hunting magic, and the sites are typically in mountainside rock shelters and shallow caves illuminated by natural light.

Iberian schematic art, on the other hand, is a more recent phenomenon, and is generally held to have been prevalent in the Iberian Peninsula between around 4,000 BC and 1,000 BC.

Its defining characteristic is that only basic fragments of each figure are represented, converting the elements into little more than outlines and, in some cases, geometrical shapes. As a logical extension of this some of the commonly used figures became highly stylized and abstract, losing their similarity to real objects but, apparently, retaining their significance.

Similar artistic development occurred in the rest of the Mediterranean Basin and Europe, although there are variations from one area to another which make it possible for experts to identify an artifact or painting as belonging to one culture or another.

Legends surrounding Monte Arabí in Yecla

The spiritual and mystic significance of Monte Arabí has survived the passing of the millennia, and even today there are many stories which are still repeated with sufficient frequency for many to believe them to contain elements of truth.

These stories range from battles in the time of Moorish rule to rumours that in the past the area was a place of pilgrimage of the same significance as Lourdes and Santiago de Compostela in modern times.

Others claim that there is a large seam of uranium or magnetite underneath the mountain, or that ley lines converge on the mountain, causing those who come here to feel uneasy, and there are faith healers who travel to Monte Arabí to “replenish their energy supplies”.

Some have speculated that the lost prehistoric city of Elo is located here, and that it is home to the writing of the Egyptian god Thoth, while historians are confident that Hannibal passed the mountain as he made his way with his elephants to Sagunto prior to crossing the Alps and attack Rome .

However, the most commonly heard myth surrounds the “Cueva del Tesoro” (the cave of treasure), which is said to be constantly guarded but contains an unimaginable fortune. Others maintain that this cave was in fact a secret tunnel out of the fortress of El Arabilejo, 500 metres away, but no way through has ever been found.

The only “evidence” is the tale of two travellers who arrived in the 19th century on horseback and entrusted their mounts to the locals while they disappeared. After three days they supposedly re-emerged carrying large sacks – supposedly containing treasure - and thanked the “yeclanos” for their kindness, rewarding them with pieces of gold.

More recently, between 1979 and 1991 there were numerous reports of UFOs over Monte Arabí, the most intense activity occurring between 1983 and 1985.

Visiting Monte Arabí

For all of the reasons mentioned above Monte Arabí receives numerous visitors, but those going there should be aware that they are unlikely to see the prehistoric art itself, as mentioned above.

However, even if not to appreciate the rock art or to experience instead the legendary mysticism and spirituality of the mountain, a visit is recommended to see the wonderful views out over the Altiplano and the spectacular setting in which our ancestors first gave vent to their artistic leanings thousands of years ago.

Monte Arabí can be reached by taking the MU-18A road out of Yecla towards Montealegre and following the signs to the left after 14 or 15 kilometres, or by following the MU-404 towards Fuente-Álamo and heading right after 15.6 kilometres: again, this turning is signposted. Click here for the location of the tourist information point.

If visiting Yecla don’t forget to make sure one of your first ports of call is the tourist office (Plaza Mayor, 1, telephone 968 754104, email turismo@yecla.es).

For more local events, news and visiting information go to the home page of Yecla Today.